Data Fundamentals

Load, clean, reshape, and merge your data

Think of Data as Excel Spreadsheets

The datasets we work with in Stata and R are just tables—exactly like Excel spreadsheets. Each row is an observation (a person, a country-year, a transaction), and each column is a variable (age, GDP, price). If you've used Excel, you already understand the basic structure. The difference is that instead of clicking and dragging, we write code to manipulate these tables—which makes our work reproducible and scalable to millions of rows.

Reading & Writing Files

Loading Data

* Load Stata dataset

use "data.dta", clear

* Load CSV file

import delimited "data.csv", clear

* Load Excel file

import excel "data.xlsx", sheet("Sheet1") firstrow clearlibrary(haven) # For Stata files

library(readr) # For CSV files

library(readxl) # For Excel files

# Load Stata dataset

data <- read_dta("data.dta")

# Load CSV file

data <- read_csv("data.csv")

# Load Excel file

data <- read_excel("data.xlsx", sheet = "Sheet1")import pandas as pd

# Load Stata dataset

data = pd.read_stata("data.dta")

# Load CSV file

data = pd.read_csv("data.csv")

# Load Excel file

data = pd.read_excel("data.xlsx", sheet_name="Sheet1")Saving Data

* Save as Stata dataset

save "cleaned_data.dta", replace

* Export to CSV

export delimited "cleaned_data.csv", replace# Save as Stata dataset

write_dta(data, "cleaned_data.dta")

# Export to CSV

write_csv(data, "cleaned_data.csv")# Save as Stata dataset

data.to_stata("cleaned_data.dta", write_index=False)

# Export to CSV

data.to_csv("cleaned_data.csv", index=False)Save Intermediate Files

Save your data after each major step with numbered prefixes. When something breaks at step 5, you can start from step 4 instead of re-running everything:

01_imported.dta02_cleaned.dta03_merged.dta

Data Cleaning

Inspecting Your Data

* Overview of dataset

describe

* Summary statistics

summarize

* First few rows

list in 1/10

* Check for missing values

misstable summarize# Overview of dataset

str(data)

glimpse(data)

# Summary statistics

summary(data)

# First few rows

head(data, 10)

# Check for missing values

colSums(is.na(data))# Overview of dataset

data.info()

data.dtypes

# Summary statistics

data.describe()

# First few rows

data.head(10)

# Check for missing values

data.isna().sum()Creating and Modifying Variables

* Create new variable

gen log_income = log(income)

* Conditional assignment

gen high_earner = (income > 100000)

* Modify variable

replace age = . if age < 0

* Drop observations

drop if missing(income)

* Keep only certain variables

keep id income agelibrary(dplyr)

data <- data %>%

mutate(

# Create new variable

log_income = log(income),

# Conditional assignment

high_earner = income > 100000,

# Modify variable

age = if_else(age < 0, NA_real_, age)

) %>%

# Drop observations

filter(!is.na(income)) %>%

# Keep only certain variables

select(id, income, age)import numpy as np

# Create new variable

data["log_income"] = np.log(data["income"])

# Conditional assignment

data["high_earner"] = data["income"] > 100000

# Modify variable

data.loc[data["age"] < 0, "age"] = np.nan

# Drop observations

data = data.dropna(subset=["income"])

# Keep only certain variables

data = data[["id", "income", "age"]]Reshaping Data

Long Data is (Almost) Always Better

Most commands expect long format: multiple rows per unit, one column for values. If you're copy-pasting variable names with years (income_2018, income_2019...), you probably need to reshape to long.

Wide vs. Long Format

id income_2020 income_2021 1 50000 52000 2 60000 61000

One row per unit. Each time period is a separate column.

id year income 1 2020 50000 1 2021 52000 2 2020 60000 2 2021 61000

Multiple rows per unit. Two columns (id + year) together identify each row.

Key Insight: Multiple Identifier Columns

In long format, a single column no longer uniquely identifies each row. Instead, two or more columns together form the unique identifier:

- Panel data:

country+yeartogether identify each observation - Individual-time:

person_id+datetogether identify each observation - Repeated measures:

subject_id+treatment_roundtogether identify each observation

This is why Stata's reshape command requires both i() (the unit identifier) and j() (the new time/category variable).

Reshaping Wide to Long

* i() = unit identifier, j() = what becomes the new column

reshape long income_, i(id) j(year)

rename income_ incomelibrary(tidyr)

data_long <- data %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = starts_with("income_"),

names_to = "year",

names_prefix = "income_",

values_to = "income"

) %>%

mutate(year = as.numeric(year))# Melt wide to long

data_long = pd.melt(

data,

id_vars=["id"],

value_vars=["income_2020", "income_2021"],

var_name="year",

value_name="income"

)

# Clean up year column

data_long["year"] = data_long["year"].str.replace("income_", "").astype(int)Aggregating Data

Often you need to compute summary statistics within groups (by state, by year, etc.) or collapse data to a higher level of aggregation.

Group Calculations with egen

The egen command ("extensions to generate") creates new variables based on functions applied across observations:

* Mean across all observations

egen income_mean = mean(income)

* Mean within groups (by state)

bysort state: egen income_mean_state = mean(income)

* Other useful egen functions:

bysort state: egen income_max = max(income)

bysort state: egen income_sd = sd(income)

bysort state: egen income_count = count(income)

bysort state: egen income_p50 = pctile(income), p(50)library(dplyr)

# Add group-level statistics while keeping all rows

data <- data %>%

group_by(state) %>%

mutate(

income_mean_state = mean(income, na.rm = TRUE),

income_max = max(income, na.rm = TRUE),

income_sd = sd(income, na.rm = TRUE),

income_count = n(),

income_p50 = median(income, na.rm = TRUE)

) %>%

ungroup()# Add group-level statistics while keeping all rows

data["income_mean_state"] = data.groupby("state")["income"].transform("mean")

data["income_max"] = data.groupby("state")["income"].transform("max")

data["income_sd"] = data.groupby("state")["income"].transform("std")

data["income_count"] = data.groupby("state")["income"].transform("count")

data["income_p50"] = data.groupby("state")["income"].transform("median")gen sum vs. egen sum

In Stata, gen sum() creates a running total, while egen sum() creates the group total. Always read the help file—function names can be misleading!

Collapsing to Group Level

Use collapse to aggregate data to a higher level (e.g., individual → state, state-year → state):

* Collapse to state-level means

collapse (mean) income age, by(state)

* Multiple statistics

collapse (mean) income_mean=income ///

(sd) income_sd=income ///

(count) n=income, by(state)

* Different statistics for different variables

collapse (mean) income (max) tax_rate (sum) population, by(state year)# Collapse to state level

state_data <- data %>%

group_by(state) %>%

summarize(

income_mean = mean(income, na.rm = TRUE),

income_sd = sd(income, na.rm = TRUE),

n = n()

)

# Different statistics for different variables

state_year_data <- data %>%

group_by(state, year) %>%

summarize(

income = mean(income, na.rm = TRUE),

tax_rate = max(tax_rate, na.rm = TRUE),

population = sum(population, na.rm = TRUE),

.groups = "drop"

)# Collapse to state level

state_data = data.groupby("state").agg(

income_mean=("income", "mean"),

income_sd=("income", "std"),

n=("income", "count")

).reset_index()

# Different statistics for different variables

state_year_data = data.groupby(["state", "year"]).agg(

income=("income", "mean"),

tax_rate=("tax_rate", "max"),

population=("population", "sum")

).reset_index()egen vs. collapse

- egen — Adds a new column but keeps all rows. Use when you need the group statistic alongside individual data.

- collapse — Reduces the dataset to one row per group. Use when you want aggregated data only.

Merging Datasets

Merging combines two datasets that share a common identifier (like person ID or state-year).

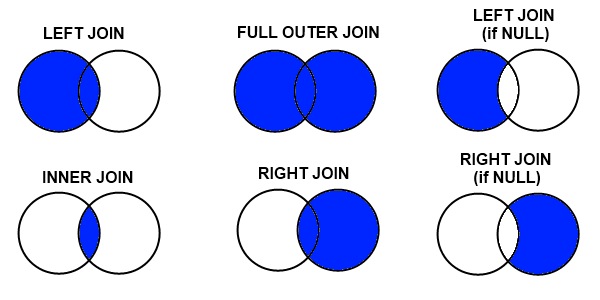

Types of Joins

The most important thing to understand is what happens to rows that don't match:

Credit: datacourses.com

- Inner join: Keep only rows that match in both datasets

- Left join: Keep all rows from the left (master) dataset

- Right join: Keep all rows from the right (using) dataset

- Full outer join: Keep all rows from both datasets

Merge Types by Relationship

Know Your Merge Type

- 1:1 — Each row matches exactly one row (person → demographics)

- m:1 — Many rows match one (students → school characteristics)

- 1:m — One row matches many (firm → firm-year panel)

- m:m — Almost always wrong! If you think you need this, reshape first.

When Merges Create Duplicates

Merges can increase your row count. This is sometimes expected and sometimes a bug.

Expected: m:1 or 1:m Merges

When merging individual data with aggregate data, rows should duplicate:

- 100 students + 5 schools → still 100 rows (each student gets their school's data)

- 50 states + 10 years of policy data → 500 state-year rows

Unexpected: Accidental Duplicates

If your row count increases unexpectedly, you probably have duplicate keys:

- Two "John Smith" entries in one dataset → each gets merged twice

- Forgot that some IDs appear multiple times

* BEFORE merging: Check for unexpected duplicates

duplicates report person_id // Should say "all unique" for 1:1

duplicates report state // OK to have duplicates for m:1

* Count rows before and after

count

local n_before = r(N)

merge m:1 state using "state_data.dta"

count

local n_after = r(N)

* If n_after > n_before in a m:1 merge, something is wrong!

di "Rows before: `n_before'"

di "Rows after: `n_after'"

if `n_after' > `n_before' {

di as error "WARNING: Row count increased - check for duplicate keys!"

}# BEFORE merging: Check for duplicates

individuals %>% count(person_id) %>% filter(n > 1) # Should be empty for 1:1

state_data %>% count(state) %>% filter(n > 1) # Should be empty

# Count rows before and after

n_before <- nrow(individuals)

merged <- individuals %>% left_join(state_data, by = "state")

n_after <- nrow(merged)

# Check if row count changed unexpectedly

if (n_after > n_before) {

warning("Row count increased! Check for duplicate keys in state_data")

# Find the problem

state_data %>% count(state) %>% filter(n > 1)

}# BEFORE merging: Check for duplicates

print(individuals.groupby("person_id").size().loc[lambda x: x > 1]) # Should be empty

print(state_data.groupby("state").size().loc[lambda x: x > 1]) # Should be empty

# Count rows before and after

n_before = len(individuals)

merged = individuals.merge(state_data, on="state", how="left")

n_after = len(merged)

# Check if row count changed unexpectedly

if n_after > n_before:

print("WARNING: Row count increased! Check for duplicate keys")

print(state_data.groupby("state").size().loc[lambda x: x > 1])The Row Count Rule

- 1:1 merge: Row count should stay exactly the same (or decrease if using inner join)

- m:1 merge: Row count should stay the same as master dataset

- 1:m merge: Row count will increase (one master row → many using rows)

- If row count increases when you didn't expect it, you have duplicate keys somewhere

Example: Merging Individual Data with State Data

Suppose you have individual-level data and want to add state characteristics:

person_id state income 1 MA 50000 2 MA 60000 3 CA 70000 4 NY 55000

state min_wage population MA 15.00 7000000 CA 15.50 39500000 TX 7.25 29500000

* Load master data

use "individuals.dta", clear

* Merge: many individuals per state → m:1

merge m:1 state using "state_data.dta"

* ALWAYS check the results

tab _merge

/*

_merge | Freq.

----------+------------

1 | 1 ← Only in master (NY - no state data)

2 | 1 ← Only in using (TX - no individuals)

3 | 3 ← Matched (MA, CA)

*/

* Investigate unmatched

list if _merge == 1 // NY had no state data

list if _merge == 2 // TX had no individuals

* Keep matched only (after understanding why others didn't match)

keep if _merge == 3

drop _mergelibrary(dplyr)

individuals <- read_dta("individuals.dta")

state_data <- read_dta("state_data.dta")

# Left join: keep all individuals, add state data where available

merged <- individuals %>%

left_join(state_data, by = "state")

# Check for unmatched

merged %>% filter(is.na(min_wage)) # NY had no state data

# Inner join: keep only matched

merged <- individuals %>%

inner_join(state_data, by = "state")individuals = pd.read_stata("individuals.dta")

state_data = pd.read_stata("state_data.dta")

# Left join: keep all individuals, add state data where available

merged = individuals.merge(state_data, on="state", how="left", indicator=True)

# Check merge results

print(merged["_merge"].value_counts())

# Check for unmatched

print(merged[merged["min_wage"].isna()]) # NY had no state data

# Inner join: keep only matched

merged = individuals.merge(state_data, on="state", how="inner")Pre-Merge Data Cleaning

Merge variables must be exactly identical in both datasets—same name, same values, same type. Most merge problems come from subtle differences that require string cleaning.

* Check if your variable is actually numeric or string

browse, nolabel // Shows actual values, not labels

* Common string cleaning operations:

* 1. Remove periods: "D.C." → "DC"

replace state = subinstr(state, ".", "", .)

* 2. Remove leading/trailing spaces: " MA " → "MA"

replace state = trim(state)

* 3. Extract substring: "Washington DC" → "DC"

replace state = substr(state, -2, 2) // Last 2 characters

* 4. Convert case: "ma" → "MA"

replace state = upper(state)

* 5. Rename to match other dataset

rename statefip state

* 6. Convert string to numeric (or vice versa)

destring state_code, replace

tostring state_fips, replacelibrary(stringr)

# Common string cleaning operations:

# 1. Remove periods

data$state <- str_replace_all(data$state, "\\.", "")

# 2. Remove leading/trailing spaces

data$state <- str_trim(data$state)

# 3. Extract substring

data$state <- str_sub(data$state, -2, -1) # Last 2 characters

# 4. Convert case

data$state <- str_to_upper(data$state)

# 5. Rename to match other dataset

data <- data %>% rename(state = statefip)

# 6. Convert types

data$state_code <- as.numeric(data$state_code)

data$state_fips <- as.character(data$state_fips)# Common string cleaning operations:

# 1. Remove periods

data["state"] = data["state"].str.replace(".", "", regex=False)

# 2. Remove leading/trailing spaces

data["state"] = data["state"].str.strip()

# 3. Extract substring

data["state"] = data["state"].str[-2:] # Last 2 characters

# 4. Convert case

data["state"] = data["state"].str.upper()

# 5. Rename to match other dataset

data = data.rename(columns={"statefip": "state"})

# 6. Convert types

data["state_code"] = pd.to_numeric(data["state_code"])

data["state_fips"] = data["state_fips"].astype(str)Labels Can Be Deceiving

In Stata, when you see "Washington" in the data browser, it might actually be stored as the number 53 with a label attached. Use browse, nolabel or tab var, nolabel to see the true values. Merges use the actual values, not the labels!

Common Merge Problems

Watch Out For

- Duplicates on key: If your key isn't unique when it should be, you'll get unexpected results. Always run

duplicates reportfirst. - Case sensitivity: "MA" ≠ "ma" in Stata. Use

upper()orlower()to standardize. - Trailing spaces: "MA " ≠ "MA". Use

trim()to remove. - Different variable types: String "1" ≠ numeric 1. Convert with

destringortostring. - Labels hiding values: What looks like "California" might be stored as 6. Check with

nolabel.

Appending (Stacking) Datasets

Use append to stack datasets vertically (same variables, different observations):

* Append multiple years of data

use "data_2020.dta", clear

append using "data_2021.dta"

append using "data_2022.dta"# Bind rows from multiple dataframes

data_all <- bind_rows(

read_dta("data_2020.dta"),

read_dta("data_2021.dta"),

read_dta("data_2022.dta")

)# Concatenate multiple dataframes

data_all = pd.concat([

pd.read_stata("data_2020.dta"),

pd.read_stata("data_2021.dta"),

pd.read_stata("data_2022.dta")

], ignore_index=True)Stata Traps

Stata has some behaviors that can silently corrupt your analysis.

Missing Values Are Infinity

In Stata, missing values (.) are treated as larger than any number. This means comparisons like if x > 100 will include missing values.

* This INCLUDES missing values (dangerous!)

gen high_income = (income > 100000)

* This is what you actually want

gen high_income = (income > 100000) if !missing(income)

* Or equivalently

gen high_income = (income > 100000 & income < .)

* The ordering is: all numbers < . < .a < .b < ... < .z

* So . > 999999999 evaluates to TRUE# R handles this more intuitively - NA propagates

high_income <- income > 100000

# Returns NA where income is NA, not TRUE

# But still be explicit about NA handling

high_income <- income > 100000 & !is.na(income)# Python/pandas handles this intuitively - NaN propagates

high_income = data["income"] > 100000

# Returns NaN where income is NaN, not True

# But still be explicit about NA handling

high_income = (data["income"] > 100000) & data["income"].notna()>, >=, or !=. Your sample sizes will be wrong, and your estimates will be biased.

egen group Silently Top-Codes

When you use egen group() to create a numeric ID from string or categorical variables, Stata uses an int by default. If you have more unique values than an int can hold (~32,000), it silently repeats the maximum value.

* DANGEROUS: If you have >32,767 unique beneficiaries,

* later IDs will all be assigned the same number!

egen bene_id = group(beneficiary_name)

* SAFE: Explicitly use a long integer

egen long bene_id = group(beneficiary_name)

* Or for very large datasets (>2 billion unique values)

egen double bene_id = group(beneficiary_name)

* Always verify you got the right number of groups

distinct beneficiary_name

assert r(ndistinct) == r(N) // This will fail if top-coded# R doesn't have this problem - factors work fine

data$bene_id <- as.numeric(factor(data$beneficiary_name))

# Or use dplyr

data <- data %>%

mutate(bene_id = as.numeric(factor(beneficiary_name)))# Python doesn't have this problem - uses 64-bit integers by default

data["bene_id"] = pd.factorize(data["beneficiary_name"])[0] + 1

# Verify

assert data["bene_id"].nunique() == data["beneficiary_name"].nunique()Numeric Precision

Stata's float type only has ~7 digits of precision. Large IDs stored as floats will be silently corrupted.

* float has ~7 digits of precision

* This can cause merge failures on IDs!

gen float id = 1234567890

* id is now 1234567936 (corrupted!)

* Always use long or double for IDs

gen long id = 1234567890 // integers up to ~2 billion

gen double id = 1234567890 // integers up to ~9 quadrillion

* Check if a variable might have precision issues

summarize id

* If max is > 16777216 and storage type is float, you have a problem

* Fix: compress optimizes storage types automatically

compress# R uses double precision by default, so this is less of an issue

# But be careful with very large integers

id <- 1234567890 # Fine in R

# For extremely large integers, use bit64 package

library(bit64)

big_id <- as.integer64("9223372036854775807")# Python uses 64-bit integers by default, so this is less of an issue

id = 1234567890 # Fine in Python

# pandas also handles large integers well

data["id"] = pd.to_numeric(data["id"], downcast=None) # Keep full precision

# Check dtypes

print(data.dtypes)Defensive Coding Habits

- Always use

if !missing(x)with inequality comparisons - Always use

egen longoregen doublefor group IDs - Run

compressafter loading data to optimize storage types - Use

assertliberally to catch problems early